More than 50 years of studying Steller sea lion behaviour has yielded one of the most complete life history descriptions for any species of marine mammal. Collectively, the behavioural observations can explain why the population trends of the eastern and western populations of Steller sea lions are diametrically opposed…

The decline of Steller sea lions in the Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands may be the ultimate sea lion murder mystery. Many people firmly believe that the population decline was caused by the pollock fishery (the over-fishing hypothesis), while others have pointed to an over-abundance of pollock as the most likely suspect (the junk-food hypothesis).

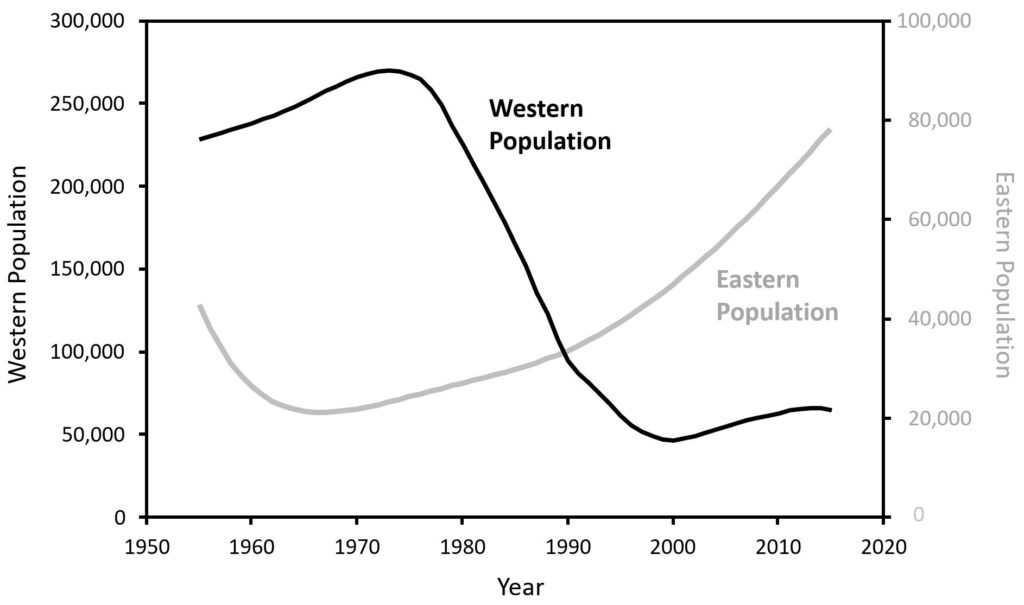

Figure 1. Estimated numbers of Steller sea lions in the Western (Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands) and Eastern populations (California to Southeast Alaska) from 1956 to 2018. Numbers were reconstructed from census counts of pups and non-pups as per Trites and Larkin (1996). Note the 3-fold difference in scales used to plot the two population trajectories.

In a recently published book on the behavioural ecology of fur seals, sea lions and walrus, Professor Andrew Trites compared sea lion behaviours in the declining region (Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands) with sea lion behaviours in an increasing region (Southeast Alaska) to determine whether the populations exhibited behavioural differences consistent with food shortages. He compared the dive depths, dive durations, time spent foraging, and the time sea lions spent nursing across seasons and years between the two regions. His review also focused on weaning — a critical life-history stage — to determine when and how weaning occurs.

Figure 2. A scarred Steller sea lion bull weighing over 700 kg among young females. (Photo by A.W. Trites).

Trites found the published behavioural studies of adult and juvenile Steller sea lions do not support the overfishing hypothesis — but are, instead, consistent with the junk-food hypothesis. The available data point to lactating females that consume large amounts of low-energy fish (such as walleye pollock and Pacific cod) having a high probability of miscarriage, and keeping their dependent young for an extra one or two years — thereby causing birth rates and population numbers to decline. In contrast, lactating females that consume larger amounts of fattier fish (such as sand lance and Pacific herring) appear able to successfully wean a pup each year.

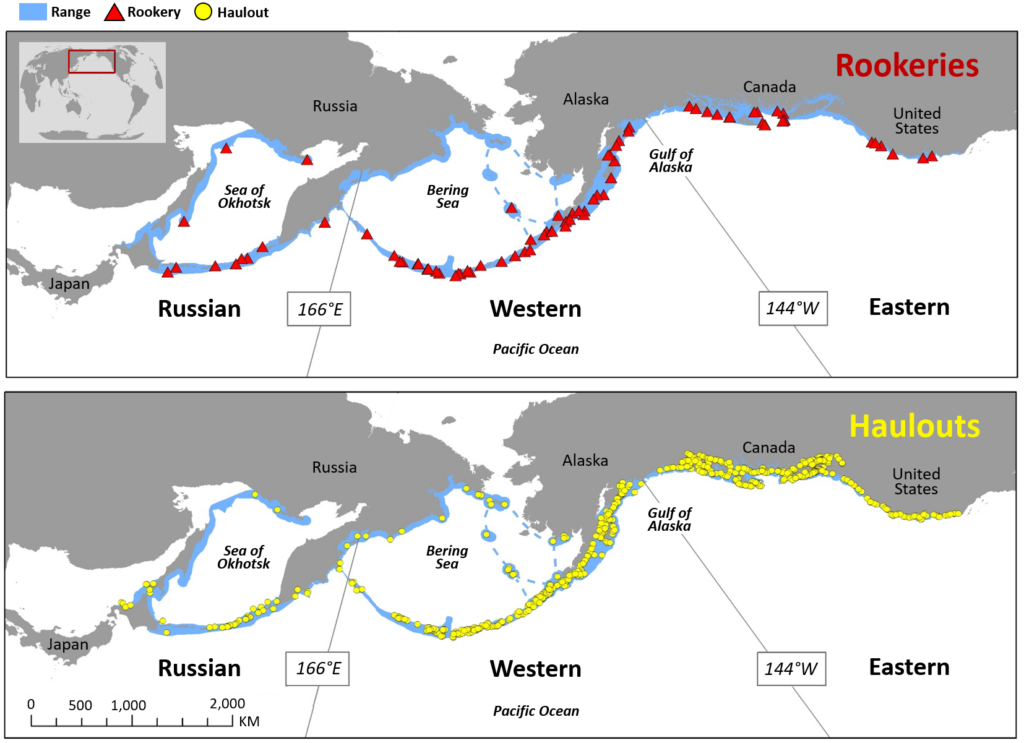

Figure 3. Locations of rookeries and haulouts used by the Russian, Western and Eastern populations of Steller sea lions in 2020. The shaded range reflects the tendency for Steller sea lions to stay within ~30 km of haulouts and rookeries, and to feed over shelf areas. Dashed lines indicate presumed site movements. Note that the range of the Russian population once extended further south to the Toyama Gulf in Japan and along the Asian coast of the Sea of Japan to the Korean Peninsula. (Map produced by S. Agbayani and A.W. Trites).

Being able to wean a juvenile sea lion at 1, 2 or 3 years appears to be an evolutionary adaptation to natural shifts in the abundance of different species that dominate the community prey structure in the North Pacific Ocean — and is an adaptation that can successfully slow population declines of Steller sea lions until the ocean shifts to an alternative state containing greater portions of energy-rich fish that allows sea lion numbers to increase again.

Figure 4. A Steller sea lion bull in July with pups, a harem of adult females—and a dependent juvenile (upper right corner). (Photo by A.W. Trites).

Dr. Andrew Trites is professor in the Marine Mammal Research Unit at the University of British Columbia

Publication

Publication

2021 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||