How many juvenile coho are harbor seals eating?

Salmonids are one of the most valuable fish species in the Pacific Northwest. However, some species of salmon such as chinook and coho are at all-time low numbers. The decline of chinook and coho coincides with an increase of the harbor seal numbers in Washington and British Columbia―and has led scientists (and fishermen) to suspect that seal predation may be tied to the decline and lack of recovery of chinook and coho salmon.

Two harbor seals equipped with a head mounted RFID tag and a back mounted GPS/3D accelerometer to collect data on foraging behavior and predation on salmon smolts.

Previous research has principally focused on harbor seal predation on adult fish, and has largely concluded that seals remove a relatively small proportion of the runs. However, more recent research is evaluating whether predation by seals on juvenile fish might be the real problem ― when smolts enter the ocean in the spring.

Austen Thomas and Hassen Allegue from the UBC Marine Mammal Research Unit (MMRU) have been studying the impact of harbor seal populations on migrating juvenile salmon. Their goal is to estimate the number of smolts eaten by harbor seals, and determine when and where those events occur. To conduct their study, Austen and Hassen focused on the Big Qualicum River where hundreds of thousands of smolts enter the ocean.

Hassen Allegue holding an antennae and listening for the VHF signal of a floating tag.

In March 2015, 37,000 PIT tags were implanted into coho smolts at the Big Qualicum hatchery in preparation for the release of 380,000 coho smolts in early May. The PIT tags are encoded with unique numbers that biologists can read using hand held wands to identify individual fish.

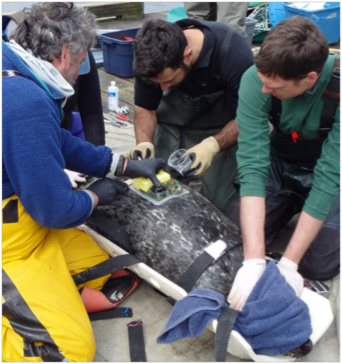

Two weeks before the release of the smolts, Austen and Hassen, with the help of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Vancouver Aquarium and others from MMRU, captured 20 harbor seals and outfitted them with specialized electronic tags (RFID tags and GPS/3D accelerometers). These tags were designed to read the PIT tags contained in fish swallowed by the seals and simultaneously record the animal behavior for approximately 6 weeks. Seals were tagged in the mouth of the river (9 animals), in addition to other nearby rocky haul-out sites.

Austen Thomas, Steve Jeffries, and Hassen Allegue attaching a GPS/3D accelerometer to a seal

The RFID tag was created by UBC researchers and engineers from Wildlife Computers. It is a head-mounted PIT tag scanner for seals and sea lions that records the ID number of each PIT tagged fish as it is swallowed, and transmits the data to researchers by satellite. In contrast, the GPS/3D accelerometer is a pair of tags used to reconstruct seal fine-scale movements by combining low resolution GPS locations and high resolution dead reckoning. Also, various seal behaviors (e.g. resting, traveling and foraging) are characterized by using data from animal acceleration combined with the depth sensor.

The higher resolution data (e.g., animal acceleration at 16Hz) cannot be transmitted by satellite and has to be downloaded directly from the tags, which means that the tags must be recovered.

The tags were glued to the fur of the seals, which meant waiting until the fall when the animals molted and grew new coats. Hassen tracked down the tags that came ashore or were floating in the ocean using VHF radio signals. He recovered 19 of the 20 tags, and hopes that someone finds the missing tag and returns it.

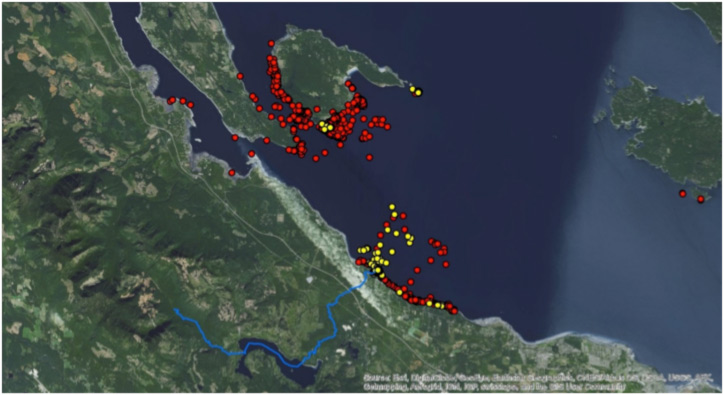

Preliminary results indicate that 20% of the tagged seals were eating coho smolts. Nearly all of the predation events occurred in the initial two weeks following the coho smolt release, and it appears that seal predation was primarily localized to those seals inhabiting the Big Qualicum River estuary.

Tagged habor seal GPS locations during the two weeks following the smolt release. The yellow dots show seals that ate PIT tagged fish, and the red dots show seals that did not eat them. Most of the yellow dots are concentrated at the mouth of the Big Qualicum River.

The direct estimates of predation mortality are being combined with diet data, seal numbers and energy requirements to determine the overall effect that seals are having on coho and chinook stocks. Additional analysis is also being done of the seal movements to determine when, where and how the predation is occurring. Such information is needed to develop potential ways to mitigate the predatory impacts of seals on salmon.

This research is supported by the Pacific Salmon Foundation through the Salish Sea Marine Survival Project.

Austen Thomas completed his PhD at UBC’s Marine Mammal Research Unit.

Hassen Allegue is a Masters Student at UBC’s Marine Mammal Research Unit.

This article originally appeared in The Marine Mammal Research Consortium’s newsletter for March 2016