Brianna Wright

Alumni

MSc.2014

Tel: 604.822.8181

Fax: 604.822.8180

E-mail: b.wright@oceans.ubc.ca

Supervisors: Dr. John Ford & Dr. Andrew Trites

Education: BSc. Biology & Anthropology, University of Victoria

Research Interests: animal behaviour, foraging ecology of apex predators, biologging tags, social structure of mammals, conservation and endangered species

Research Area: Northeast Pacific (coastal waters of British Columbia)

Salmon for supper: What can tagging technology tell us about the foraging behaviour of resident killer whales?

Juvenile northern resident killer whale I104 with DTAG

Problem

The fish-eating (also termed “resident”) killer whales of coastal British Columbia are specialist predators that feed primarily on Chinook salmon. Changes in the availability of this comparatively rare prey species are known to affect resident killer whale survival rates. To ensure the continued survival and growth of this threatened population, conservation planning would benefit from knowledge about how resident killer whales search for and locate prey. I used an innovative tagging technology, the DTAG, to record fine-scale movement patterns and vocalizations of foraging northern resident killer whales. Analysis of this DTAG data provides the first quantitative description of underwater feeding behaviour by northern resident killer whales. Foraging dive behaviour is expected to specifically target Chinook salmon and therefore may be ineffective for capturing less preferred, but more abundant prey species. Describing the specificity of feeding behaviour may help to explain the absence of prey-switching by resident killer whales in years of poor Chinook availability.

Research Questions

Approaching a whale for DTAG deployment

I am addressing the following questions:

1) Quantify and compare the characteristics (e.g. depth, dive duration, body orientation) of foraging dives with non-foraging movements.

2) Determine whether the average depth of searching and fish kills coincides with the depth range where Chinook and other salmon species are expected to be found.

3) Determine at what stage(s) of a foraging dive echolocation behaviour occurs.

4) Determine whether kills are usually brought to the surface or consumed at depth.

5) Determine if there is an acoustic cue (e.g. pulsed call, echolocation buzz or prey handling sound) consistently associated with prey capture.

Approach

To answer these questions, I used underwater movement and acoustic data collected by digital archival tags (DTAGs), a technology developed by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. These tags record data about the animal’s movement patterns, depth and body orientation as it swims, and also continuously record underwater sound. Tags are temporarily attached (less than 24 hours) to whales by four suction cups and are retrieved from the water after activation of a pre-timed release mechanism. I combined DTAG deployments with boat-based focal follows of tagged individuals, so that surface observations of foraging activity could be correlated with archived tag data. DTAGs were deployed on 32 different northern resident killer whales off northeastern Vancouver Island and the central coast of British Columbia over four field seasons (2009-2012), for a total of 126 hours of tag data (11,320 dive events). Prey remains (fish scales and tissue fragments) were collected from the water following 17 of these dives, confirming them to be successful foraging dives. I used the movement characteristics of these 17 dives to search the remaining unclassified dives and identify other potential foraging dives.

Results and Implications

- 547 potential foraging dives were identified from the 11,320 dive data set

- On average, foraging dives were deeper (76.6 ± 64.1 m), lasted longer (3.2 ± 1.9 min), and had greater overall swim speeds (2.3 ± 0.8 m/s) than non-foraging dives

- Foraging whales also rolled their bodies to a greater extent (38.7 ± 27.6 degrees)

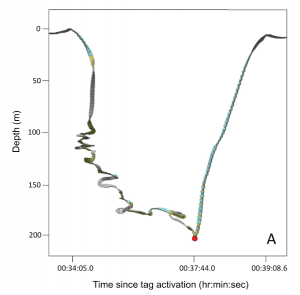

- Descent phases of foraging dives were highly convoluted and had numerous loops and changes of direction – indicating that whales are responding to the evasive maneuvers of fleeing salmon

- Spiral dive paths and body rolls during descents may also serve to widen the area of water being searched by the echolocating whale’s biosonar

- The point of fish capture (red dot in image) was usually indicated by an abrupt shift from a convoluted and looped descent to a very directional and linear ascent phase

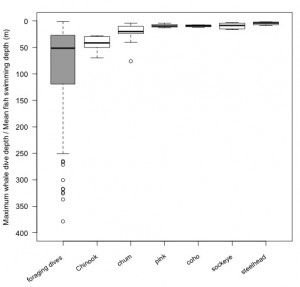

- Of the 6 species of Pacific salmon, whale foraging dive depths corresponded the best to Chinook vertical distributions, based on average swimming depths (43.4 ± 15.4 m) from salmon tagging studies (see image below) and catch depths (>30 m) from scientific test fisheries

Publications

- Ford, J.K.B., Wright, B.M., Ellis, G.M. and Candy, J.R. 2009. Chinook salmon predation by resident killer whales: seasonal and regional selectivity, stock identity of prey, and consumption rates. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2009/101. 43 pages.

Selected Presentations

- Wright, B.M. 2013. Foraging dives by northern resident killer whale show kinematic and acoustic adaptations for the capture of preferred prey. Northwest Student Chapter of the Society for Marine Mammalogy Annual Meeting. Seattle, WA.

- Wright, B.M. 2013. Kinematics and acoustics of foraging behaviour by a specialist predator, the northern resident killer whale. UBC Zoology Graduate Student Symposium (awarded Best M.Sc. Talk). Vancouver, BC.

- Wright, B.M. 2013. Diving kinematics and the acoustic behaviour of foraging northern resident killer whales. 34th Annual Pacific Ecology and Evolution Conference. Bamfield, BC.

- Wright, B.M., Ford, J.K., Ellis, G.M., Shapiro, A.D., Deecke, V.B., and Trites, A.T. 2011. Quantifying the foraging behaviour of northern resident killer whales (Poster). 19th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals. Tampa, FL.

- Wright, B.M. 2011. Quantifying the movement and echolocation behaviour of a selective predator, the northern resident killer whale. Northwest Student Chapter of the Society for Marine Mammalogy Annual Meeting. Vancouver, BC.

- Ford, J.K.B., Ellis, G.M. and Wright, B.M. 2009. Kin-directed food sharing and extreme natal philopatry in a population of fish-eating killer whales. 18th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals. Quebec City, QC.

Links

Photo credits

From top to bottom of page: Erin Rechsteiner; Brianna Wright (DFO Marine Mammal Research Permit MML-01); Lance Barrett-Lennard; 3D DTAG track visualization was created using TrackPlot 2.3 software (copyright Colin Ware, University of New Hampshire).

| I appreciate the help and support provided by: | ||||