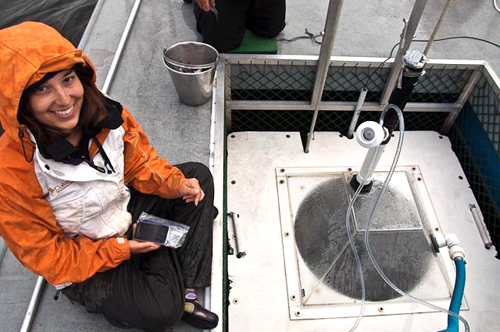

Carling Gerlinsky on the diving platform with Hazy and two Steller sea lion trainers from the Vancouver Aquarium. The diving study was conducted in Indian Arm, the southernmost fjord in North America. Shown on the platform are the pipes (left) that were screwed together to various depths and the custom-made pump (right) used to send fish down the pipes to depths of up to 50 m. The sea lions were trained to surface inside the dome (center) between each dive.

Open water research provides clues to behavior in wild populations

Western Alaska’s declining Steller sea lion populations live in remote and inaccessible parts of the North Pacific Ocean, making them elusive research subjects. As a result, many basic questions about their diet, behavior and physiology remain unanswered.

These questions attracted Carling Gerlinsky to the Consortium’s Open Water Research Station, which offered her a unique opportunity to study the diving behavior and physiology of Steller sea lions. Her findings were recently published in the Journal of Comparative Physiology B.

“What drew me to the Open Water Research Station was the ability to work with trained animals that are diving realistically in the open ocean,” says Gerlinsky, “while still being able to control aspects of their behavior.”

Carling used her smart phone to record how long each sea lion spent in the dome and the number of breaths they took. She later analyzed the concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the dome to determine the energetic cost of each dive.

Aerobic Dive Limit

Gerlinsky sought to answer a basic but important physiological question: how long can a Steller sea lion hold its breath before it depletes its oxygen reserves? This is an important question to answer because of the implications it has for interpreting the meaning of the relatively short duration of dives observed for Steller sea lions in the wild. However, measuring the breath holding ability of marine mammals (the aerobic dive limit – ADL) is difficult. Because of this, researchers often use a proxy measure called the calculated ADL (cADL).

“Calculated ADL gives a good indication of what sea lions are capable of doing based on body oxygen stores, compared to what we actually see them doing in the wild,” says Gerlinsky. “For example, if we see wild sea lions making consistently longer dives, close to or beyond their aerobic limit, it might indicate scarce prey.”

Working with eight trained female Steller sea lions, Gerlinsky estimated the oxygen stores in the blood, muscles and lungs of each. This involved taking blood samples, body composition measurements, and measuring the amount of oxygen consumed over a series of dives to different depths. She then combined these measurements using a mathematical formula to calculate that the dive limit of a Steller sea lion using its onboard oxygen was just 3 minutes for a single dive!

All of the sea lions wore harnesses when free swimming that carried scientific instruments to measure time, depth and movement.

“Our finding follows closely with what we see wild Steller sea lions doing in Alaska where they have declined,” Gerlinsky said. “We’ve worked with trained animals for many years and we know they are capable of diving for five, six, and sometimes seven minutes. In the wild, dive durations range significantly but they average two or three minutes, and usually not more than four minutes.”

Gerlinsky also found that the level of activity—diving vigorously in open water versus in a shallow aquarium setting—didn’t affect the aerobic dive limit, suggesting that the ability to store oxygen is more likely a genetic trait than a function of activity.

“This is just one instance in which basic, fact-driven research can contribute to solving a larger puzzle, she says. “We never know when some fundamental piece of knowledge about sea lions might end up being important in the field.”

PUBLICATION

PUBLICATION

|

|

|

||||||||||||