As the far lesser-known adage goes, “It ain’t easy being marine.” This especially applies to the wild Steller sea lion, which faces harsh environmental conditions, predators galore, and regular periods during which it is forced to go with less food. But the stocky Steller is a survivor.

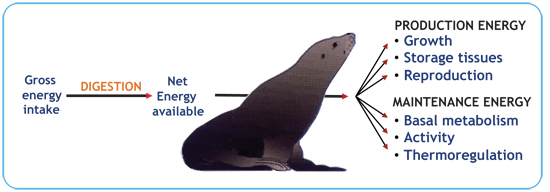

The question for marine researchers is: how? Typically, a pinniped sensing hard times ahead first attempts to conserve energy by increasing its digestive efficiency and reducing the energy it loses as waste. But sometimes these measures aren’t enough, and the animal must make a tough decision: how best to allocate the limited energy it acquires through food. Should it go to growth? Stored energy? Or thermoregulation? The sea lion must get its priorities straight — and fast.

Scientists have long speculated on potential strategies, but until recently, no one had actually determined how marine mammals allocate energy when faced with food shortages. The team behind this study comprised Consortium researchers Tiphaine Jenniard du Dot, David A.S. Rosen, and Andrew W. Trites, all of the University of British Columbia. Their results were published in Physiological and Biochemical Zoology.

Schematic and simplified partitioning of the gross energy intake in an animal

Desperate Times Require Desperate Measures

Hypothesizing that pinnipeds might allocate energy differently according to the seasons and the quality of food available, the researchers divided a group of female Steller sea lions in two groups, and limited each group’s food intake for 28 days in winter and summer. The first group dined on small amounts of herring (a high-quality fish), while the second received pollock (an energetically lower-quality prey).

The researchers found that during the summer, both groups compensated for the lack of energy intake by using up their internal energy stores. In winter, both groups allocated less

energy to overall maintenance functions such as metabolism and allocated more energy to sustaining thermoregulatory capacity (the ability to keep body temperature constant). As in the summer, they once again released stored energy.

But the researchers also observed a crucial difference between the two groups of sea lions. During the summer, Team Herring allocated more energy to foraging and less to thermoregulation — a practical decision for wild sea lions given the tendency for fish to be more abundant and waters warmer in summer. In winter, when fish are likely scarcer and less predictable, the behavior of the sea lions was consistent with an animal that foraged less, such as reducing activity levels and maintaining thermoregulatory capacity. Team Pollock, on the other hand, did not make the same sensible energy decisions.

By studying the energy-allocation choices made by both groups, the researchers concluded that the sea lions dining on herring when times were tough adjusted better to environmental conditions than those fed pollock. This suggests that low-energy food sources might not trigger the physiological and behavioral mechanisms needed to adjust to food shortages, which would take a toll on the animal’s fitness in the long run.

SEE RELATED PUBLICATION:

|

|

|

||||||||||||