Protecting natural habitats rarely occurs without sparking controversies—usually among those whose livelihoods depend on resources within the protected areas. Conservation can thus come at a significant economic cost.

In the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea, restricting fisheries within areas deemed to be critical habitat for Steller sea lions may or may not have resulted in serious financial losses for the fishing industry. This uncertainty reflects the fact that there has been no reliable method to estimate the opportunity costs, or the costs of not fishing in protected areas.

To address this obvious need, Matthew Berman of the Institute of Social and Economic Research at the University of Alaska teamed up with researchers from the University of British Columbia (Edward Gregr, Gakushi Ishimura, Ryan Coatta, Rowenna Flinn, Rashid Sumaila, and Andrew Trites). Their aim was to develop a “scientifically defensible” method of valuing habitat-driven fishery closures, and to apply this method to a relevant issue, namely the effects of the 2001 Steller sea lion habitat closures on groundfish trawl fisheries in the North Pacific. Their findings were published in Fisheries Centre Research Reports.

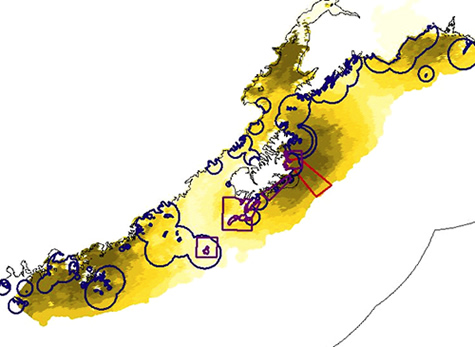

Figure 1: Estimated spatial economic values of shore-based Pacific cod fisheries in the Gulf of Alaska during the summer-fall 2001, showing higher value areas in darker colors. Circles surrounding sea lion haulouts and rookeries identify Steller sea lion critical habitat, while the rectangles show other areas closed to fisheries. The red rectangle shows the Chiniak Gully Research Area, which was closed to commercial fishing to allow the Alaska Fisheries Science Center to conduct research on the effects of the pollock fishery on pollock abundance and distribution.

Considering Space

According to the researchers, there is a growing consensus that management of fisheries needs to consider spatial differences in habitat and the resources they provide at different times of the year. Past economic analyses of habitat closures have attempted to account for spatial considerations, but have not addressed the variations and complexities of the ocean environment. Berman’s team designed a new method to differentiate habitat among a large number of small areas within the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea, and among different fisheries (at-sea and shore-based trawl fleets).

The researchers hypothesized that environmental variables would play important roles in their analysis—that conditions such as surface temperature, wave height, and salinity can explain and predict the spatial distribution of fish, which in turn influences the distribution of fishing effort. They analyzed environmental variables using satellite images, oceanographic modeling, and bathymetry techniques (to measure sea floor and depth) at 3-km and 9-km spatial scales and two-week and one-month intervals—and used these data to predict fish biomass and fisheries catch per unit of effort (CPUE), which, combined with spatial regulatory and cost factors, could explain the spatial distribution of fishing effort over time.

A Crucial Tool for the Future

Through an extensive statistical analysis of the variables, Berman’s team found that the 2001 Critical Habitat Closures cost the North Pacific groundfish trawl fisheries 5 to 40 percent of their total potential net earnings, although cost estimates varied widely between at-sea and shore-based trawl fleets. They also found strong empirical support for their hypotheses—that environmental conditions can predict the spatial distribution of fish, which can in turn predict the distribution of fishing effort.

The researchers report that the new set of methods they developed to estimate the value of ocean fisheries can easily be generalized to evaluate fishery closures in time and space for any protected species or for marine conservation generally. Certainly, with pending proposals to close additional areas to fishing in the North Pacific, this is potentially a crucial tool to ensure that responsible decisions are made to manage fisheries, protect people’s livelihoods, and safeguard species that are at risk.

March 3, 2009

PUBLICATIONS

PUBLICATIONS

|

|

|

||||||||||||