Pacific cod are among the most heavily fished species in the Northern Hemisphere, and once-thriving populations have significantly declined in many parts of the world. In the Gulf of Alaska, the Pacific cod fishery is generally thought to be sustainable, but managers have limited resources and only a few decades of recorded data from which to base their conclusions.

Pacific cod are among the most heavily fished species in the Northern Hemisphere, and once-thriving populations have significantly declined in many parts of the world. In the Gulf of Alaska, the Pacific cod fishery is generally thought to be sustainable, but managers have limited resources and only a few decades of recorded data from which to base their conclusions.

Researchers addressed this problem using a new interdisciplinary approach that reconstructed the past. By combining palaeoecological data with biological data, they extended limited data sets from a half-century to several thousand years, giving scientists and fisheries managers a better idea of how current trends fit into the bigger picture.

In order to assess the general sustainability of the modern fishery in the Gulf of Alaska, researchers sought to determine whether industrialized fishing has affected the size of Pacific cod and whether climate change affects cod size and abundance. This study, authored by Herbert Maschner (Idaho State University), Matthew Betts (Canadian Museum of Civilization), Katherine Reedy-Maschner (Idaho State University), and Andrew Trites (University of British Columbia), was recently published in Fishery Bulletin.

“The fish that stops”

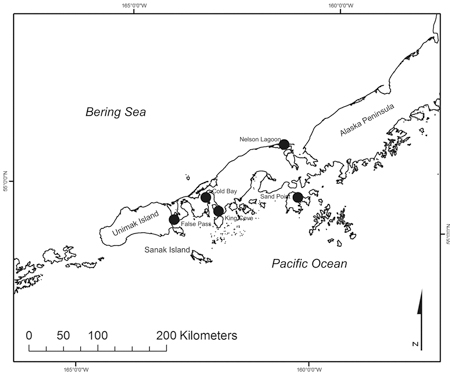

The study took place on Sanak Island, in the western Gulf of Alaska, where the Aleut people have lived and fished for thousands of years, and where well-preserved shell mounds (or “middens”) now offer windows into their ancient ways and the conditions they faced. The researchers chose eight such sites spanning the period between 2550 B.C. and 1540 A.D. They excavated and measured the size and abundance of large numbers of fish bones from all sites, comparing these sizes to those of modern cod. They also looked into the effects of climatic changes over that time span.

The North Pacific and the western Gulf of Alaska region showing Alaska and the location

of Sanak Island where bones were collected at archeological sites to determine whether

a change in fish size was evident over the 4500 archeological record.

The findings showed that although the size and relative abundance of Pacific cod fluctuated over the years, modern cod are fairly similar in size to their ancient ancestors. They also showed that Pacific cod tend to periodically vanish in great numbers, only to reappear in greater numbers later (which explains why the Aleut word for Pacific cod translates to “the fish that stops”).

This disappearing act seems to be linked to natural changes in ocean climate called regime shifts. While periods of warming seem to cause cod numbers to fall, the researchers found that Pacific cod populations do appear to recover quickly when the climate cools again. According to the study, regime shifts do not appear to affect cod body size.

A sign of sustainability

The palaeoecological data led the research team to conclude: “The changes in fish length between the prehistoric and modern eras in the Gulf of Alaska are more consistent with natural fluctuations than with harvesting pressure,” indicating that “current Pacific cod fisheries management and harvesting techniques in the western Gulf of Alaska are working.”

The palaeoecological data also points to an association between low ocean temperatures and low cod abundance, leading the authors to conclude that global warming may well become a complicating factor in the ability of fisheries managers to sustain abundant cod populations.

![]() RELATED PUBLICATION:

RELATED PUBLICATION:

|

|

|

||||||||||||