Electronic tags reveal secrets of foraging fur seals

Northern fur seals in the eastern Bering Sea spend most of their lives foraging underwater and breeding on remote islands. To study their behavior, scientists depend on electronic tags to track an individual animal’s movements as it searches for food.

Modern technology now allows researchers to follow the second-by-second movements of seals at sea to determine where they go and what they are doing.

In a recent Consortium study, Brian Battaile (University of British Columbia) and colleagues analyzed the data recorded by electronic tags that were temporarily attached to 83 northern fur seals in the eastern Bering Sea. The study was published in the scientific journal Marine Mammal Science.

Chad Nordstrom, Brian Battaile and Andrew Trites ― part of the field team on St. Paul Island.

By combining the data from different types of tags, the researchers were able to retrace the animals’ movements at an extremely high resolution, revealing an unprecedented glimpse of northern fur seals in the wild.

Fine-Scale Foraging

A female northern fur seal from St. Paul Island, Alaska, carrying biologging tags to collect data on where and how she obtains food in the Bering Sea. The tags are later removed and any residual glue on the fur falls off when the animal molts.

“Our study was part of a much larger project in the Bering Sea that investigated how walrus, seabirds and northern fur seals find their prey and make a living,” says Battaile. “We used sophisticated tags that collect data 16 times per second, which gave us incredibly detailed information about what the seals were doing.”

Using this data, the scientists reconstructed and compared the foraging tracks of fur seals from two breeding islands in the eastern Bering Sea—St. Paul and Bogoslof Islands. St. Paul Island historically hosted the world’s largest breeding population of northern fur seals, but has been declining at an annual rate of 4.2% since 1998. Just 250 miles south of St. Paul, the small Bogoslof Island population has been increasing at an annual rate of 10.1% since 1997.

“We expected the animals that were going offshore from St. Paul Island to behave similarly to those going offshore from Bogoslof Island,” says Battaile. “We figured they’d be targeting the same types of prey.”

“We found there were two types of fur seals at St. Paul—one that foraged offshore and the other that stayed over the continental shelf. According to our calculations, the behavior of the Bogoslof seals was similar to the on-shelf St. Paul animals, while the offshore St. Paul seals had different foraging behaviors.”

Data Dilemma

A leading theory suggests that lactating females on St. Paul Island are unable to capture enough calorie-rich food to produce enough lipid-rich milk to support their pups. As a result, the pups cannot store enough fat prior to weaning and have difficulty surviving their first year as they learn to forage. This makes it critically important to better understand the foraging behaviors of lactating females.

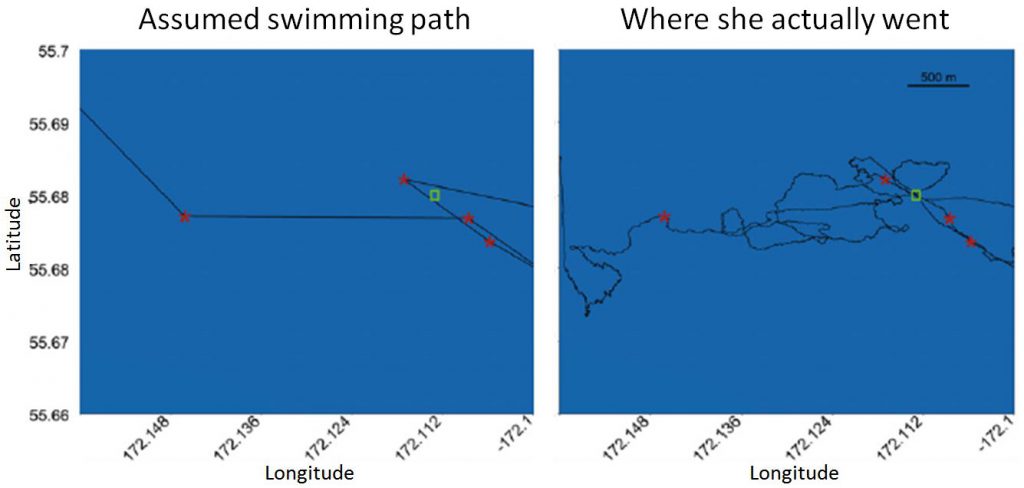

A bird’s eye view of where one of the tracked female fur seals traveled. The red stars show the recorded GPS locations of the seal, and the green box highlights a location that the seal crossed 4 times. Until now, biologists have been joining the GPS locations and assuming that seals swim in straight lines between them. However, data from the Daily Diary tag allowed the actual swimming paths to be calculated, and showed how much more swimming the seals do than previously recognized from straight line calculations.

“We knew the St. Paul animals traveled further away from land than the Bogoslof animals, but the new tags showed us that the distances swum were much greater than ever reported. This tells us that the animals from St. Paul are working even harder to obtain food than anyone previously thought―and corroborates the nutritional stress theory.”

Each increase in technology brings a better understanding of the lives of marine mammals. New generations of electronic tags and improved statistical techniques have brought new insights into the foraging habits and movement of northern fur seals—but not without challenges.

A wet northern fur seal (center) that has just arrived on shore at St. Paul Island after about 7 days feeding at sea calls to find her pup.

“Marine mammal research has often been at the forefront of technological developments. In our case, the resolution of the data we collected and our analysis of fur seal foraging behavior was at a finer-scale than anyone has ever been able to do before. Similar technological advances should allow oceanographers to collect finer-spatial scale data on chlorophyll concentrations and sea-surface temperatures to match our fur seal data,” says Battaile. “Then we will be able to put all the puzzle pieces together to get the complete picture of how fur seals are exploiting the Bering Sea and why the feeding conditions are so different between the two fur seal islands.”

PUBLICATION

PUBLICATION

|

|

|

||||||||||||